"The most durable thing in writing is style..."

04 Feb 2018"The most durable thing in writing is style, and style is the most valuable investment a writer can make with his time."

Opined the great American author Raymond Chandler. Style, a word overloaded with meaning and a concept overwrought with commentaries, weighs heavily upon all would be writers regardless of whether they are crafting prose or programming code. In this case, Chandler used the word style style in the sense of the authorial voice. The je ne sais quoi that distinguishes one writer from another. And while all writers must find their own voice, we cab generalize Chandler’s advice think of style as structured pattern or a particular design, then we shift the egocentric meaning of style tS larger issues of function and form. After all, the quality of writing can never be measured by simple utilitarian calculus.

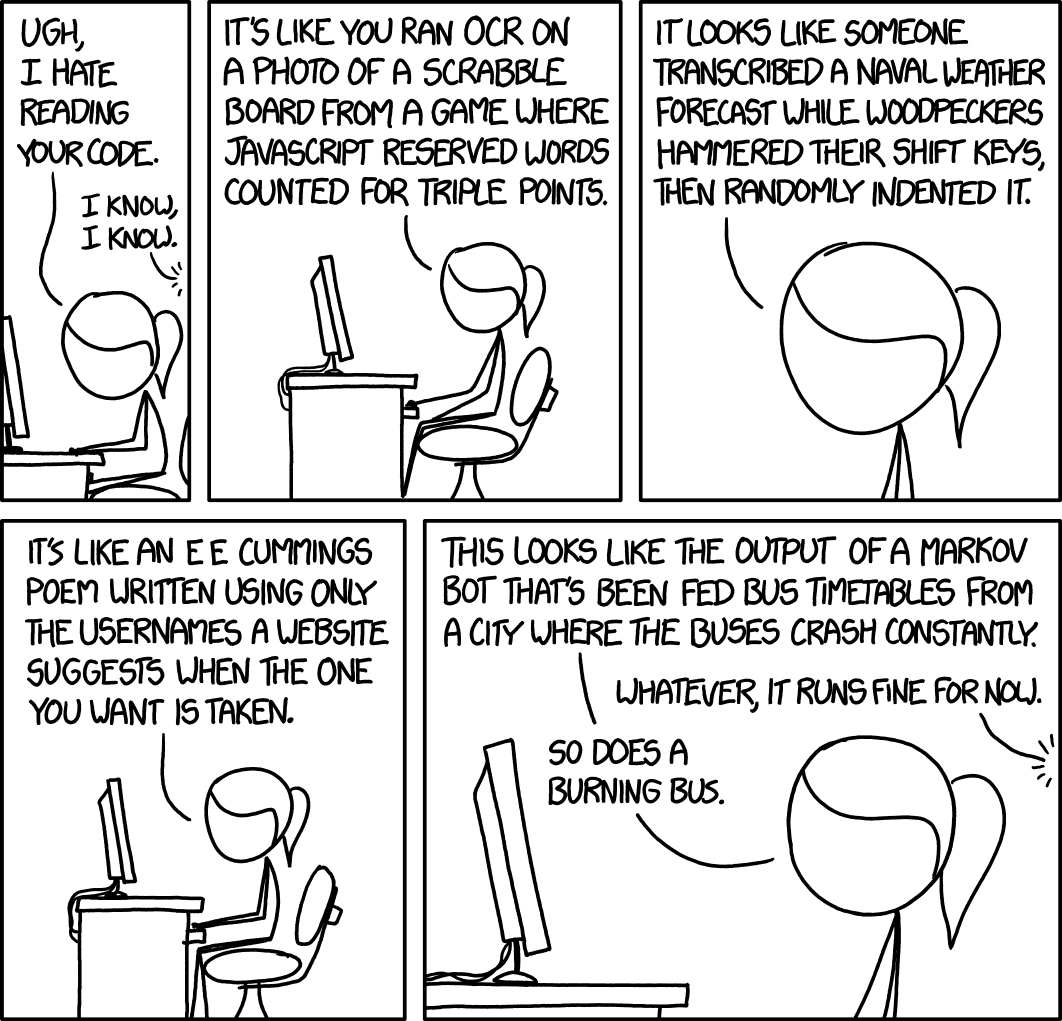

"Whatever, it runs fine for now."

In Randall Munroe’s brilliant xkcd comic strip: “Code Quality 2” (featured to the right), Pony-Tail once again reluctantly reviews Cueball’s code. What follows is a volley jibes at Cueball’s code to which he retorts: “Whatever, it runs fine for now.” But can we trust it? Will it always work? Are there any unintended side-effects? Does sloppyCoding == sloppyThinking? If only Cueball followed up with his promise from the original “Code Quality” strip and “read a style guide,” he would not have endure Ponytail’s vicious and seemingly well-deserved barbs.

Coding is hard enough already. A tough algorithm can be difficult to implement, and even harder to glean from code. Poor style exacerbates the problem of reviewing and maintaining code. Sloppy code is the “worst.” And if you wrote said sloppy code, then it also embarrassing. Enforced style guides can at least spare us all some of the shame. Style provides a set of ground rules designed to ensure consistency, clarity, and can even save us from hours of debugging. Styles often require us to to follow “best” practices or prevent us from using features that might be error prone. The C programming language, for instance, still has goto, but as Kernighan and Ritchie note in their canonical The C Programming Language:

C provides the infinitely-abusable goto statement, and labels to branch to. Formally, the goto is never necessary, and in practice it is almost always easy to write code without it. We have not used goto in this book.

Just because a language supports a feature, it does not always mean we should use it. The promise of JSLint is to help coders avoid the worst parts of the JavaScript language as noted on its help page:

JavaScript is a sloppy language, but hidden deep inside there is an elegant, better language. JSLint helps you to program in that better language and to avoid most of the slop.

JSLint makes no apologies, and goes far as to warn a would-be user that:

JSLint will hurt your feelings. Side effects may include headache, irritability, dizziness, snarkiness, stomach pain, defensiveness, dry mouth, cleaner code, and a reduced error rate.

This probably true for all Linters and any style guide that you do not write yourself (and maybe even then).

CheckStyle or how to make sure your code is not "like a salad recipe written by a corporate lawyer using a phone autocorrect that only knew Excel formulas."

My first run in with a linter came in ICS 211, the second programming class in the UHM ICS curriculum. One of the teaching assistants convinced our professor that it was a good idea to use CheckStyle to review our Java code (and deduct points for CheckStyle errors). Unfortunately, we did not start using CheckStyle until the fourth week, so we had to go back and refactor all our old code to make it CheckStyle compliant. I can still hear the groans and the muttering of four letter words. Things got better as we learned how to better use the Eclipse IDE. As we got used to using CheckStyle it got easier. Like a grammar checker in your word processor, it flagged the errors as we typed. We were learning style and coding practices as we typed.

Inevitably, I came down with a bad case of nerd rage when I discovered that the style we were using forbade us from using the ternary operator. I had just learned about the ternary operator during break between ICS 111 and ICS 211. Needless to say, I was keen to use it. I went so far as to ask the my teaching assistant for an exception. He denied my appeal. At the time I was not happy. It seemed ludicrous. I still think the ternary operator has a place in Java coding, but in retrospect, I can see why you have to set a standard and stick with it. If you make too many exceptions, you do not have a style guide anymore.

By the end of the semester, everyone’s code “looked” way more professional. The style guide we used was particularly draconian about comments. Every method had a comment, every parameter, every exception, every return statement, and so on. We were all struck by the tedium of writing comments. Code is supposed to speak for itself right? If only. The one problem that I did have was that my comments started seem repetitive. I often found the comments harder to write than code. This is one of the two biggest limits of any linter. CheckStyle can make sure you wrote a comment, but it cannot evaluate it, nor provide tips.

Below is a method I wrote for our hash table project, which was the hardest project of the semester.

/**

* Wrapper for Put method, which adds the specified Key and associated Value

* to this table, if successful, it returns null. If the specified key is

* already stored in this table, then it replaces the old value and returns

* it. If last put exceeds threshold, table is rehashed. If the hash table

* is full, throws an ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException exception.

* @param key The Key paired to the specified Value to put into this table.

* @param value The Value paired to the specified Key to put into this table.

* @return Null if the specified key and associated value is successfully put

* into this table; if the key is already in this table, then it replaces the

* associated value and returns the old value.

* @throws ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException If this hash table is full.

* @throws IllegalArgumentException If specified key is null.

*/

public V put(final K key, final V value) {

// checks if rehash is necessary

if (rehashSwitchedOn && checkLoadThresholdStatus()) {

rehash();

}

// should always be false if rehash method is active and working properly

// throws exception when table is both full and put is NOT a replacement

if (isFull() && (getKeyIndex(key) == DEFAULT_NIL)) {

throw new ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException("Warning this table is FULL!");

}

if (key == null) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("New Key May Not Be Null");

}

return put(computeIndex(key), key, value);

}

Looking back, I am still not satisfied with all my comments. I am happy that I learned from CheckStyle the importance of the using the keyword final. After I started using final in Java, I never had an accidental re-assignment again. Getting used to always using {} with all your if statements was another easy adjustment and one that paid off.

One of my happiest moments in ICS 211 was when I showing some friends my code. They could not believe change in quality, and in just one semester to boot! By the end of ICS 211, my only real complaint about CheckStyle was why we did not use it in ICS 111.

The code below is from the first project for ICS 111:

// plays- soundName1 position

public void playKey1() {

if(play==true){

keyNote1.stop(); // resets play point

keyNote1.play();

scaling();

}

}

For reasons I cannot recall, this method was over-indented by one whole level and for some reason, I left all code within the if {} at the same level as if statement. How absolutely horrifying. CheckStyle could have saved me from that. The great thing about CheckStyle and most linters is that you can set your own style, and a style guide could have been written for students just learning to code.

By my final ICS 111 project, my code look this:

// re-targets drone if chicken moves off screen

private void reTargeting() {

chicks.add(mine); // returns the off-screen chicken to chicks arraylist

if(!chickens[chicks.get(0)].cooped) {

mine=chicks.get(0);

chicks.remove(0);

if(borderGuard(chickens[mine].getX(),chickens[mine].getY())) {

desty = y + (chickens[mine].getY() - getY());

destx = x + (chickens[mine].getX() - getX());

whereTheCoopAt(mine);

} else {

watchDog(); // behavior when the only chickens are off screen

}

}

}

The virtue of this code is that at least everything is properly aligned. There is only one nested if statement. There should be a space between “mine” and “chicks” on the “mine=chicks.get(0);” line. It is a little odd that I call variable y and the method getY() on the same line. The comments are not the best, but at least there are some comments. The bigger issue is the names of all the variables and method. This takes us to second major limitation with linters. Naming conventions are important, and coming up with right name can be harder than you think. No linter that can tell if your name is a good one or not. Is name descriptive? Is it misleading? Most of the names in teh above method are not helpful besides getX() and getY(). The whereTheCoopAt and watchDog methods do not describe what the methods do. I wrote watchDog and one of teammates wrote the ingenious whereTheCoopAt. At the time, I thought both names were pretty clever, but now they are just too clever by half as old the cliché goes.

Mystery of Good Code

Figuring out what is good code and how to write good code remains an unsolved mystery. Humans are still learning. We are still trying to solve this conundrum using the so-called Feynman.

The Feynman Algorithm:

- Write down the problem.

- Think real hard.

- Write down the solution.

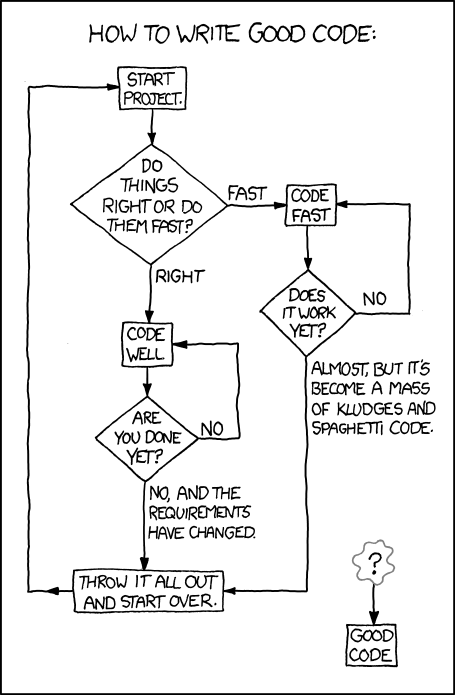

Of course, as the joke goes, this is a lot easier if you have the brain of Richard Feynman. For the rest of us, the writing of good code is much like follow chart in the xkcd comic “Good Code.”

The beauty of style is that it gives us a good place to start. Linters enforce that style, which sadly is the only way to ensure everyone complies. Styles and “best practices” will change as programming and its priorities change. One cannot help but wonder with the development of AI that can write programs, how will that effect the way we code. Until AI writes all our code for us, linters are the best way to enforce style and protect us from our more wild impulses.